Programming III

Matthew Barnes, Mathias Ritter

Introduction to functional programming 5

Features of Haskell 5

Bare basics 5

Standard prelude 6

Standard list functions 6

Function application 7

Useful GHCi Commands 7

Naming requirements 7

Layout rules 8

Types, Classes and Functions 9

Types 9

Basic types 9

Compound types 10

List values 10

Curried functions 10

Polymorphism 11

Classes 12

Functions 14

Guarded equations 14

‘where’ vs ‘let’ and

‘in’ 16

Pattern matching 17

Lambda expressions 18

Operator sections 19

List Comprehension and Recursion 19

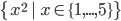

List comprehension 19

Zips 20

Recursion 20

Tail recursion 21

Higher Order Functions 23

Map, filter and fold 23

Dollar operator 23

Function composition 24

Declaring Types 24

Declaring Types and Classes 24

‘type’ 24

‘data’ 25

‘newtype’ 26

‘class’ 26

‘instance’ 26

Trees 27

Red-Black Trees 27

Abstract Syntax Trees 28

Functors 28

Directions, trails and zippers 30

Graphs 31

Indexed collections of Nodes, Edges 31

Structured data type with cyclic dependencies 31

Inductive approach with graph constructors 33

Evaluation Order and Laziness 35

Equational reasoning 35

Redex 36

Beta-reduction 36

Call-By-Name 37

Call-By-Value 38

Modularity 38

Strict application 39

Interpreters and Closures 40

Part 1 - Substitutions 40

Lambda calculus 40

Beta reduction syntax 41

Alpha conversion 41

Part 2 - Machines 42

Environments 42

Frames 43

Continuations 44

CEK-machines 44

Closures 45

Example sequence 47

Functional I/O and Monads 50

I/O in Haskell 50

IO a 50

Actions 51

Do notation 51

Main Function, File Handling, Random Numbers 52

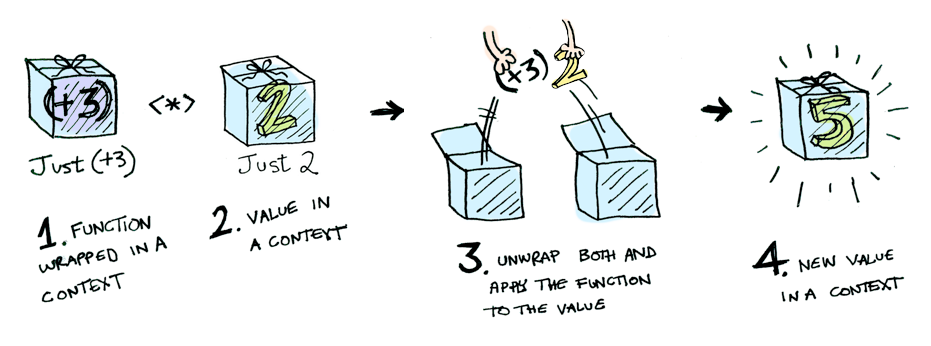

Applicatives 53

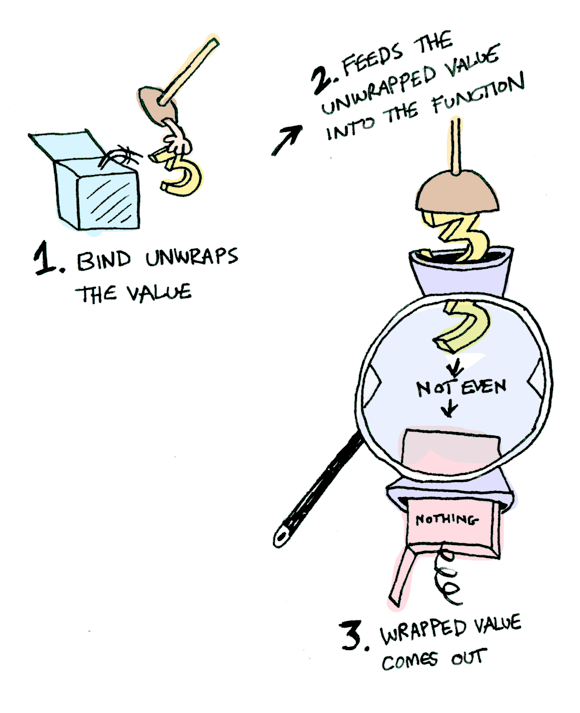

Monads 56

Use of monads: Error handling 58

Use of monads: Chaining 59

Use of monads: Non-determinism 60

mapM 61

fitlerM 64

Functional Programming in Java 67

Functions as Objects 67

Functional Interfaces 68

ActionListener 69

Lambda Syntax 70

More general function types 70

Closure: lambda vs anonymous inner classes (AICs) 72

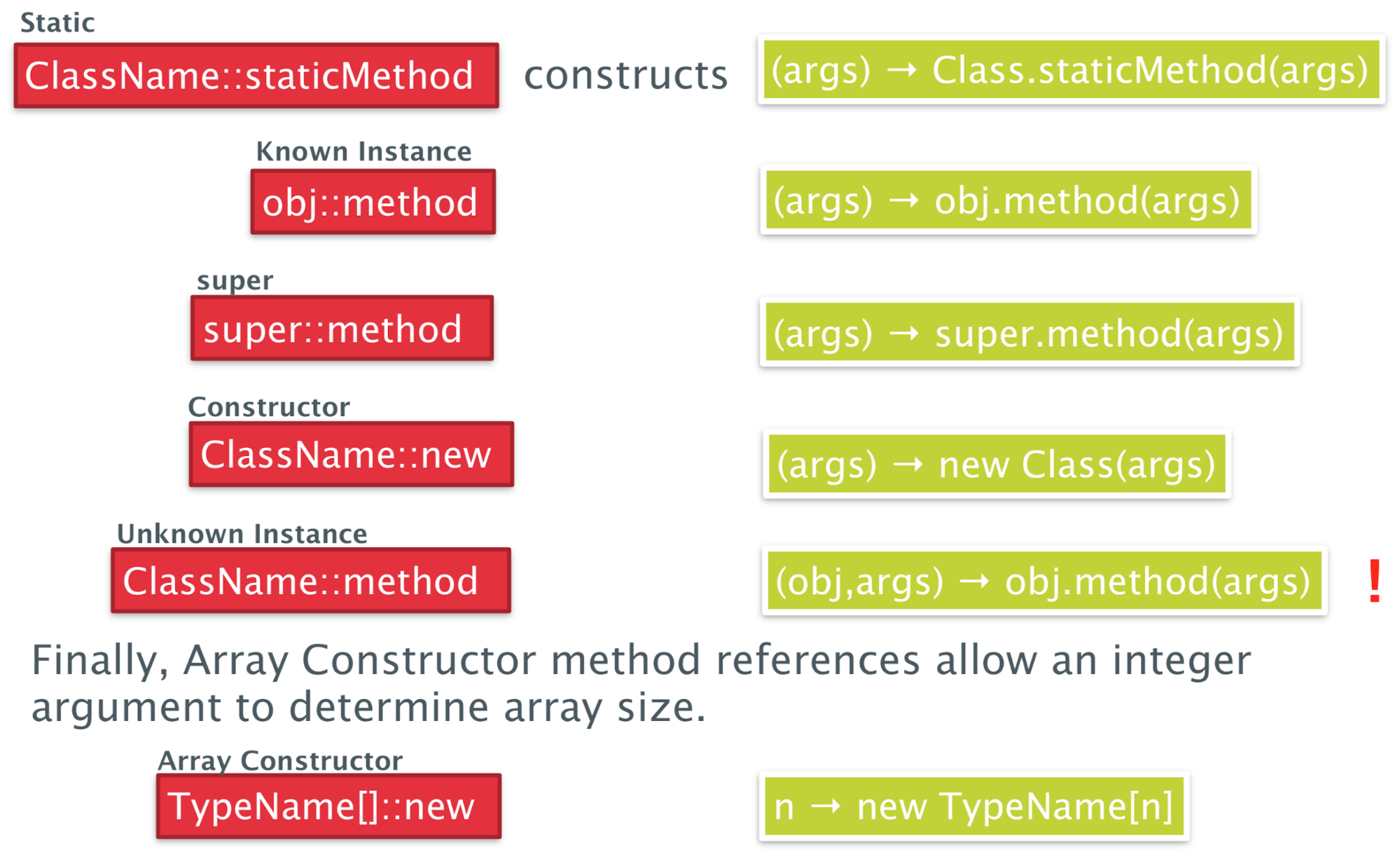

Method references 74

Recursion 75

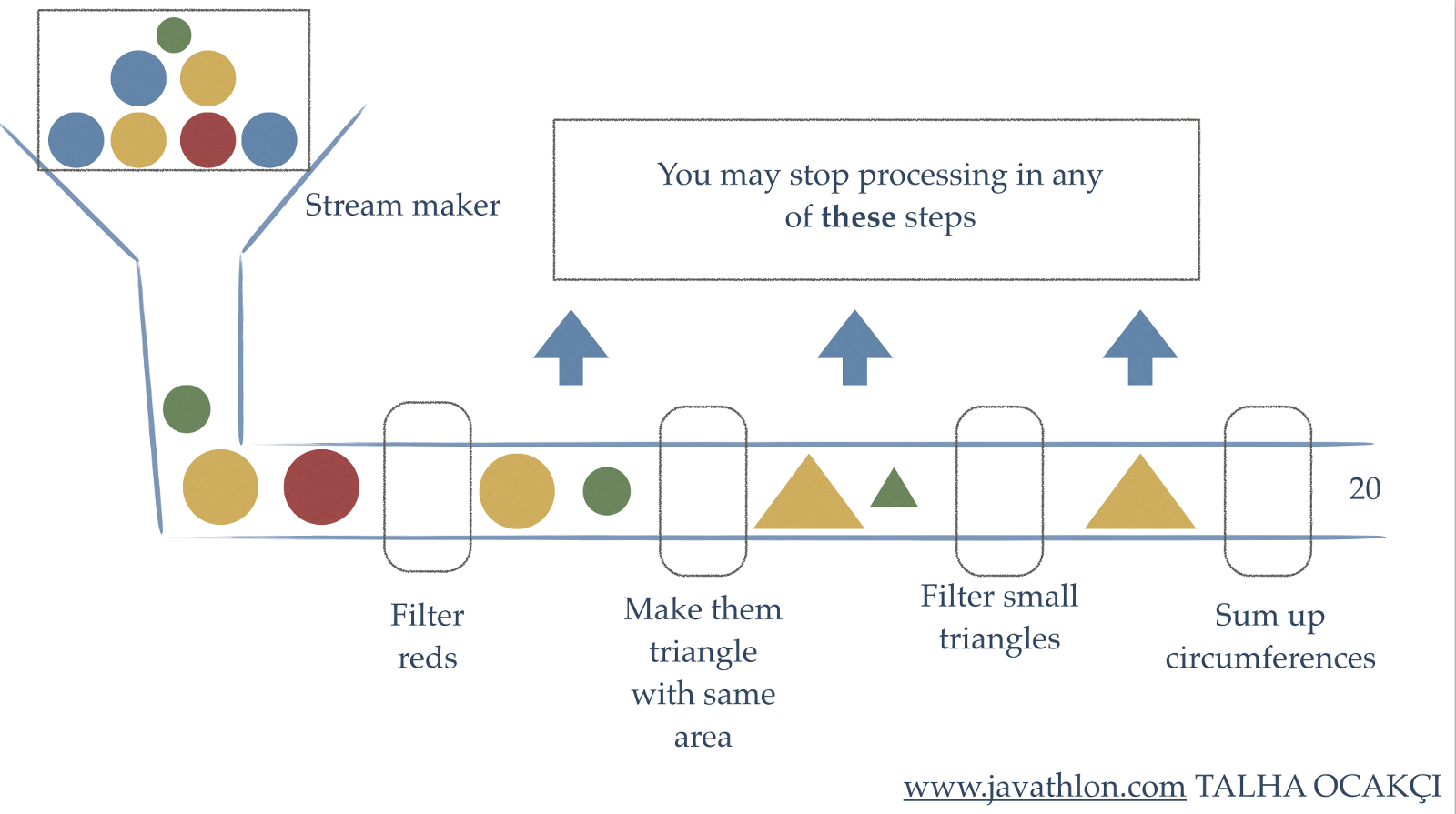

Programming with Streams 77

Functional programming and lists 77

External vs internal iteration 77

Streams in Java 77

Common operations 79

Map - Streams as Functors 79

flatMap - Streams as Monads 80

More stream operations yay 80

State of Streams 81

Optional 82

Parallel streams 82

Functional Programming in JavaScript 84

Functional vs Imperative Style 84

Functional Features 85

Functional Programming in JS with Rambda 85

Iterative Approach 86

Get a property 88

Filtering 88

Rejecting 90

New objects from old 90

Sorting 91

Functional Approach 91

TL;DR 93

Introduction to functional programming 93

Types, Classes and Functions 94

List Comprehension and Recursion 96

Higher Order Functions 96

Declaring Types 97

Evaluation Order and Laziness 98

Interpreters and Closures 99

Functional I/O and Monads 99

Functional Programming in Java 101

Programming with Streams 102

Functional programming in JavaScript 103

Functional programming in JS with Rambda 103

Recommended Reading 104

Introduction to functional programming

Features of Haskell

-

Concise Programs - few keywords, support for scoping by indentation

-

Powerful Type System - types are inferred by the compiler where possible

-

List Comprehensions - construct lists by selecting and filtering

-

Recursive Functions - efficiently implemented, tail recursive

-

Higher-Order Functions - powerful abstraction mechanism to reuse code

-

Effectful Functions - allows for side effects such as I/O

-

Generic Functions - polymorphism for reuse of code

-

Lazy Evaluation - avoids unnecessary computation, infinite data

structures

-

Equational Reasoning - pure functions have strong correctness properties

Bare basics

-

You can evaluate simple expressions like this:

-

5 +

6 (infix)

-

3 -

1 (infix)

-

8 `mod`

2 (infix)

-

(+) 5

6 (prefix)

-

(-) 3

1 (prefix)

-

mod 8

2 (prefix)

-

To create your own functions, do this:

-

[function name] [parameters] = [function body]

-

... will add up two numbers.

-

To execute a function, do this:

-

[function name] [function parameters]

-

This will add 50 and 10, given the definition of

‘add’ above.

-

You don’t need brackets or commas, like in Java or C;

this is enough.

|

Set theory

|

Haskell

|

|

|

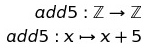

add5 :: Int -> Int

add5 x = x + 5

|

Standard prelude

-

The Standard prelude is a library of common built-in

functions.

-

It contains arithmetic functions, like +, -, div, mod

etc.

-

It also has comparison functions, like >, <=, == etc.

-

A couple of examples include:

- 3 * 7

- (*) 3 7

-

mod 10 2

-

10 `mod` 2

-

1 - ( 2 * 3 )

-

(1 - 2 ) * 3

-

5 >= (1 + 2)

-

5 >= (-5)

-

Operations like +, -, * and / are all functions, and can be

treated as such by wrapping them in brackets like (+), (-),

(*) and (/).

Standard list functions

-

There are a bunch of standard list functions that, when

applied, can be really handy.

|

Function

|

Description

|

Example

|

|

head

|

Selects the first element in the list

|

head [1, 2, 3, 4]

-- will output '1'

|

|

tail

|

Removes the first element in a list

|

tail [1, 2, 3, 4]

-- will output [2, 3, 4]

|

|

length

|

Calculates the length of a list

|

length [1, 2, 3, 4]

-- will output 4

|

|

!!

|

Selects the nth element of a list

|

[1, 2, 3, 4] !! 2

-- will output 3

|

|

take

|

Selects the first n elements of a list

|

take 2 [1, 2, 3, 4]

-- will output [1, 2]

|

|

drop

|

Removes the first n elements of a list

|

drop 2 [1, 2, 3, 4]

-- will output [3, 4]

|

|

++

|

Appends two lists

|

[1, 2] ++ [3, 4]

-- will output [1, 2, 3, 4]

|

|

sum

|

Calculates the sum of the elements in a

list

|

sum [1, 2, 3, 4]

-- will output 10

|

|

product

|

Calculates the product of the elements in a

list

|

product [1, 2, 3, 4]

-- will output 24

|

|

reverse

|

Reverses a list

|

reverse [1, 2, 3, 4]

-- will output [4, 3, 2, 1]

|

|

repeat

|

Creates an infinite list of repeated

elements

|

repeat 5

-- will output [5, 5, 5, 5, ...]

|

Function application

-

When running a function f with parameters a and b, you need

to write it like this:

-

Because of this, you need to be careful about how Haskell

interprets things:

-

f a + b = f(a) + b

-

f a + b ≠ f(a + b)

-

Haskell is left associative, which means:

Useful GHCi Commands

|

Command

|

Meaning

|

|

:load name

|

Load script name

|

|

:reload

|

Reload current script

|

|

:set editor name

|

Set editor to name

|

|

:edit name

|

Edit script name

|

|

:edit

|

Edit current script

|

|

:type expr

|

Show type of expression

|

|

:?

|

Show all commands

|

|

:quit

|

Quit GHCi

|

Naming requirements

-

You should name your variables in lower camelCase:

-

myVariableName

- var1

-

helloWorld

-

You can also define new operators like this:

|

(£) x y = x + y

5 £ 6 -- output will be 11

|

-

By convention, you should name your lists with a suffix

‘s’ on the end:

Layout rules

-

In Haskell, whitespace matters, so you need your lines to

be at the same column:

|

-- do this

a = 10

b = 20

c = 30

-- do not do this

a = 10

b = 20

c = 30

|

-

This also applies to the ‘where’ clause:

|

Implicit grouping

|

Explicit grouping

|

|

a = b + c

where

b = 1

c = 2

d = a * 2

|

a = b + c

where

{b = 1;

c = 2}

d = a * 2

|

Types, Classes and Functions

Types

-

A type is a name for a collection of related values.

-

It’s the same concept as types in Java or C.

-

To show that variable ‘e’ has type

‘t’, you would write:

-

Though normally, you wouldn’t have to do this because

Haskell figures it out. This is called “type

inference”.

-

You can use the :type command to find the type of an

expression:

|

:type head

['j','g','c']

-- will output head

['j','g','c'] ::

Char

|

Basic types

-

Basic types are like primitives in Java or C.

-

Compound types are build up from basic types, and are

combined using type operators.

-

The most common type operators are list types, function

types and tuple types.

|

Basic type

|

Description

|

Type name

|

Examples

|

|

Booleans

|

Can be either true or false, it is 1 bit in

size. Can be used with &&, || or

‘not’ operators.

|

Bool

|

True :: Bool

False :: Bool

|

|

Characters

|

Stores one character. It’s 2 words in

size.

|

Char

|

‘j’ :: Char

‘#’ :: Char

‘4’ :: Char

|

|

Strings

|

Stores a bunch of characters. They’re not

really a basic type, because they’re just

lists of characters.

|

String

|

“The World”:: [ Char ]

“MUDA” :: [ Char ]

“duwang” :: [ Char ]

“Joseph Joestar” :: [ Char ]

|

|

Numbers

|

Int, Integer, Float, Double etc are all

numbers

The difference between “Int” and

“Integer” is that “Int”

is fixed in size and “Integer” is

dynamic.

|

Int

Integer

Float

Double

|

7 :: Int

3.4 :: Float

9.56 :: Double

3587352 :: Int

|

Compound types

|

Compound type

|

Description

|

Type name

|

Examples

|

|

Lists

|

A collection of an element, of which all are

the same type

|

[ T ]

(where T is the type of the elements)

|

[ 6, 7, 3 ] :: [ Int ]

[‘j’, ‘x’] :: [ Char

]

|

|

Tuples

|

Tuples are fixed-size (immutable) lists. They

can have any type at any position.

|

( T1, T2, T3 ... )

With Tn being the types of the tuple

elements

|

(4, 7.8, “ora”) :: (Int, Float,

[Char])

|

|

Functions

|

Functions take an input and spit an output out.

The type of the input and output can be

anything, even compound types.

|

T -> U

(With T being the input type and U being the

output type)

|

add :: (Int,Int) -> Int

add (5,6) = 11

ora n = intercalate " " (take n

(repeat "ora"))

ora :: Int -> [Char]

|

List values

-

The ‘:’ operator is called the

‘cons’ operator, and it appends an element to

the beginning of a list.

- For example:

-

7 : [8, 9, 10] = [7, 8, 9, 10]

-

In fact, the cons operator forms the foundation of lists in

Haskell.

-

All lists are just syntactic sugar for the cons operator

being applied to an empty list.

- Example:

-

[3, 4, 5] is just syntactic sugar for 3 : 4 : 5 : []

Curried functions

-

Function output types can be any type. But what if that

type was another function?

-

That’s what’s called a ‘curried’

function. A curried function only takes one argument, but it

returns another function that carries out the rest.

-

It’s type looks like this:

|

add :: Int -> (Int -> Int)

or

add :: Int -> Int -> Int

|

-

Which means you could do ‘add 5’, then get the

function, then use that function on ‘6’

afterwards to get ‘11’.

-

You may ask “How do I curry functions in

Haskell?”

-

The truth is, you’ve been doing it all this time.

Every function you see in Haskell is a curried function.

There is no such thing as a function in Haskell that takes

more than 1 parameter.

-

Don’t believe me? Try :type (+) in GHCi (if you

don’t know, (+) is the function you use when you do

something like 5 + 6). You’ll see it is of type Num a

=> a -> a -> a, which is the structure of a curried

function.

-

You can also try :type (+) 5, and you’ll see that the

type of that is Num a => a -> a. By passing only one

parameter to the + operator, you are getting a function from

that curried function that adds anything it’s given by

5.

-

When you run (+) 5 6, or 5 + 6, Haskell is actually getting

a function from the curried function, and then using that

returned function. This is possible in this syntax because

Haskell is left associative by default.

-

You can do currying with lots more parameters. It’ll

look like this:

|

mult :: Int → (Int → (Int → Int))

mult x y z = x*y*z

|

Polymorphism

-

What if we don’t know what type we want?

-

For example, the ‘length’ function can be

applied with any list type, [Bool], [Int], [Char] etc.

-

Therefore, we can use a type variable to stand for “any type”:

-

The ‘a’ in the above example is like a

“placeholder” for any type.

-

A function is polymorphic if it uses one or more type

variables.

-

Think of it like a generic in Java.

-

Lots of library functions in the standard prelude use type

variables:

|

fst :: (a,b) → a

head :: [a] →

a

take :: Int → [a] → [a]

zip :: [a]

→ [b] → [(a,b)]

id :: a →

a

|

-

Remember, type variables must start with a lower-case

letter.

Classes

-

What type is (+)? It can’t use type variables,

because you can’t add Chars together. It’s sort

of Int, Integer, Float and Double all at once.

-

(+) actually uses classes to solve this problem.

-

A class in Haskell isn’t a class like in Java. In

fact, it’s more like an interface.

-

If a type inherits a class, it has specific properties that

are common to all types that also inherit that class, just like a Java

interface.

-

For example, if a function takes in an input that inherits

class ‘Num’, then every input we put into that

function must support the functionality that the class

‘Num’ expects (e.g. we can pass in numbers, like

‘5’, ‘7.6’, ‘3.4’

because they support ‘Num’, but not values like

“hello” or ‘j’ because they do not

support ‘Num’).

-

To show that a variable inherits a class, you write:

-

This shows that the variable ‘a’ inherits the

class ‘Num’.

-

Here is the full type of (+):

|

(+) :: (Num a) => a -> a -> a

|

-

As you can see, the “Num a” shows that the

variable ‘a’ refers to a number (it must be Int,

Integer, Float or Double).

-

The arrow “=>” just means that “the

left side of this is the type variable and class, the right

side of this is the type itself”, it doesn’t

have anything to do with functions.

-

You can inherit multiple classes, like this:

|

showDouble :: (Show a, Num a) => a -> String

showDouble x = show (x + x)

|

-

The ‘showDouble’ method takes in a number,

doubles it, then shows it using the ‘show’

function.

-

In order to be doubled, a variable must be a number,

therefore it must inherit the ‘Num’ class.

-

In order to be shown, a variable must be able to convert to

a string, therefore it must also inherit the

‘Show’ class.

-

As you can see, “(Show a, Num a)” shows that

the type variable ‘a’ must inherit both Show and

Num classes.

-

The good thing about Haskell is that you usually

don’t have to declare inherited classes explicitly.

Haskell will automatically see what classes a type variable

needs and inherits them accordingly.

-

You can try it yourself; create a quick function that adds

numbers together, or shows variable values. Then, use :type

to see the type of that function, and you’ll see that

the classes are already inherited.

-

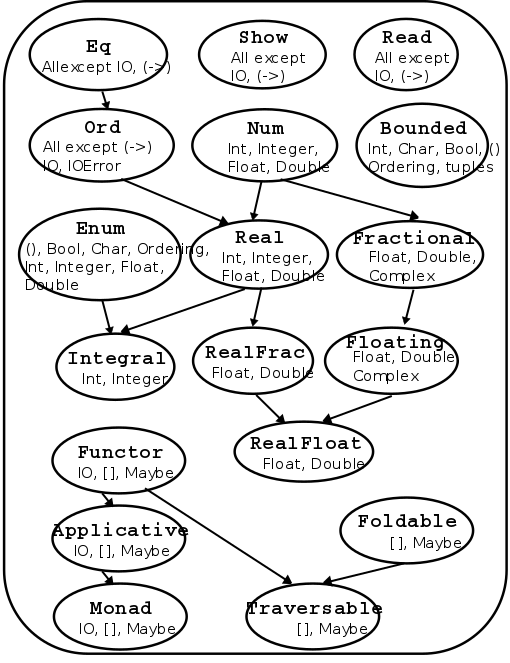

Here are some more classes:

|

Class name

|

Description

|

Example

|

|

Eq

|

Supports == and /= operations

|

isEqual x y = x == y

isEqual :: Eq a => a -> a -> Bool

|

|

Ord

|

Supports operators like < and >

|

isBigger x y = x > y

isBigger :: Ord a => a -> a -> Bool

|

|

Show

|

Supports being converted into a string

|

toString x = show x

toString :: Show a => a -> String

|

|

Read

|

Supports strings being converted into

this

|

fromString x = read x

fromString :: Read a => String -> a

|

|

Num

|

Is either Int, Integer, Float or Double

|

double x = x * 2

double :: Num a => a -> a

|

|

Integral

|

Is either Int or Integer (supports div and

mod)

|

divmod x y = (div x y + mod x y)

divmod :: Integral a => a -> a -> a

|

|

Fractional

|

Is either Float or Double (supports / and

recip, which means

‘reciprocal’)

|

negrecip x = -1 * recip x

negrecip :: Fractional a => a -> a

|

-

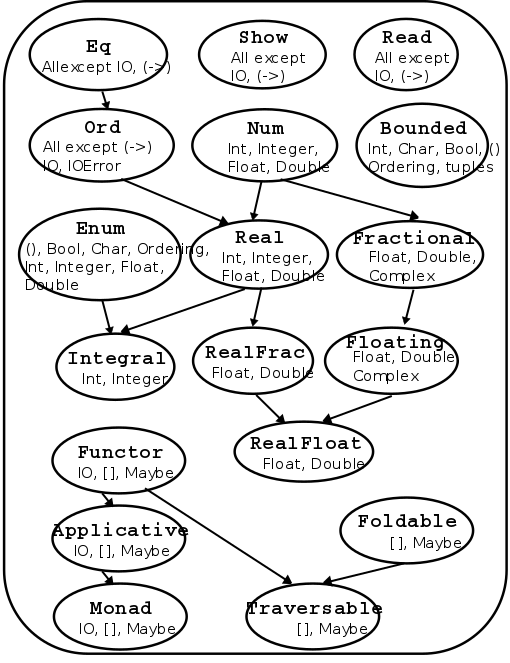

The classes are not all mutually exclusive. Ord supports

< and >, but so does Real, because they’re

numbers. Which do we pick; Ord or Real?

-

In reality, Real “extends” Ord, or is the

‘child’ of Ord. Real has all the functionality

of Ord, and then some.

-

Here is a hierarchy of the classes:

Functions

Guarded equations

-

Haskell has if statements, but they can get very messy very

quickly. You should never use them.

-

Instead, you can use guarded equations, which allow you to

change the behaviour of a function based on a predicate

(condition that returns true or false).

-

For example, let’s take the factorial recursive

algorithm. It can do two things: return 1 when the input is

0 (base case), or multiply the input by factorial(input - 1)

(recursive clause).

-

In Haskell, you can do this in two ways:

|

Pattern matching

|

Guarded equations

|

|

fact 0 = 1

fact n = n * fact (n - 1)

{- Keep in mind that this only works for a .hs

file, it will not work on the GHCi interface

unless you use :{ and :} -}

|

fact n | n == 0 = 1

| n == 1 = 1

| otherwise = n * fact (n - 1)

{- In theory, you should be able to leave out

the n == 1 bit, but GHCi didn't like it when

I tried that. -}

|

-

Let’s take the guarded equation method and pick it

apart to see how this works:

|

Steps

|

Value of n

|

Explanation

|

|

fact n | n == 0 = 1

| n == 1 = 1

| otherwise = n * fact (n -

1)

|

2

|

Here, we start by inputting the value of

‘n’ into the factorial

function.

|

|

fact n | n == 0 = 1

| n == 1 = 1

| otherwise = n * fact (n -

1)

|

2

|

Now, we look at the first guarded equation

predicate. If this is true, we do whatever is on

the right of the equals sign next to it. If this

is false, we move on to the next

predicate.

|

|

fact n | n == 0 = 1

| n == 1 = 1

| otherwise = n * fact (n -

1)

|

2

|

It’s false, so we look at the next

predicate below it. The same rule applies

here.

|

|

fact n | n == 0 = 1

| n == 1 = 1

| otherwise = n * fact (n - 1)

|

2

|

It’s false, so we move on to the next

predicate. The same rule applies here.

‘otherwise’ is like

‘else’ in Java or C, it’s used

when all other predicates are false. It’s

syntactic sugar for “True”.

|

|

fact n | n == 0 = 1

| n == 1 = 1

| otherwise = n * fact (n - 1)

|

2

|

‘otherwise’ is always true, so we

do what’s on the right of the equals sign

here. This is the recursive clause, so we do the

function again, but with n - 1.

|

|

fact n | n == 0 = 1

| n == 1 = 1

| otherwise = n * fact (n -

1)

|

1

|

Here, we input the value of ‘n’

into the factorial function again.

|

|

fact n | n == 0 = 1

| n == 1 = 1

| otherwise = n * fact (n -

1)

|

1

|

We check the first predicate. If it’s

true, we do whatever is on the right. If not,

move on to the next predicate.

|

|

fact n | n == 0 = 1

| n == 1 = 1

| otherwise = n * fact (n -

1)

|

1

|

That was false, so we move on to the next

predicate.

|

|

fact n | n == 0 = 1

| n == 1 = 1

| otherwise = n *

fact (n - 1)

|

1

|

That predicate was true, so we do what’s

on the right of the equals sign next to it. It

just says 1, so we return 1.

|

-

The order of the guards matter (just like if statements in

Java), as the interpreter will go from top to bottom.

-

Using guarded equations, we can put error cases in our

functions, like in this function that solves quadratic

equations:

|

quadroots :: Float -> Float -> Float -> String

quadroots a b c | a == 0 = error "Not quadratic"

| b*b-4*a*c == 0 = "Root is " ++ show (-b/2*a)

| otherwise = "Upper Root is "

++ show ((-b +

sqrt(abs(b*b-4*a*c)))/2*a))

++ "and Lower Root is "

++ show ((-b -

sqrt(abs(b*b-4*a*c)))/2*a))

|

-

This is a little ugly, though... isn’t there some way

we can locally define constants?

‘where’ vs ‘let’ and

‘in’

-

‘where’ allows you to locally define constants within the

scope of your functions.

-

Using the quadratic example above, we can do:

|

quadroots :: Float -> Float -> Float -> String

quadroots a b c | a==0 = error "Not quadratic"

| discriminant==0 = "Root is " ++ show centre

| otherwise = "Upper Root is "

++ show (centre +

offset)

++ " and Lower Root is "

++ show (centre -

offset)

where discriminant = abs(b*b-4*a*c)

centre = -b/2*a

offset = sqrt(discriminant/2*a)

|

-

Now, the local variables ‘discriminant’,

‘centre’ and ‘offset’ are available

within the scope of the function!

-

Doing this helps tidy up code and aid readability.

-

Make sure to indent the left of ‘where’

appropriately, or the Haskell interpreter will

complain.

-

‘let’ and ‘in’ allows you to also define local variables inside a

scope.

- Example:

|

add x y = let z = x + y in

z

|

-

In this example, we have a function ‘add’ that

takes in ‘x’ and ‘y’.

-

In that function, we let ‘z’ equal

‘x’ + ‘y’ within the scope of the

next line.

-

In that next line, we’re not really doing much;

we’re just returning z.

-

We can add more local variables using brackets, just make

sure you use semi-colons:

|

quadadd a b c d =

let { e = a + b; f = c + d } in

e + f

|

-

This has exactly the same effect as this, where we nest

‘in’ clauses:

|

quadadd a b c d =

let e = a + b in

let f = c + d in

e +

f

|

-

The difference between ‘let’ + ‘in’

and ‘where’ is that ‘let’ +

‘in’ is an expression; you can put it anywhere where an expression is expected. On the other hand,

‘where’ is syntactically bound to a function,

meaning you can only use it in one place.

Pattern matching

-

You can define a function in several parts by using pattern

matching.

-

Pattern matching allows you to define what the parameter

should look like, and then act accordingly.

- For example:

|

not :: Bool -> Bool

not False = True

not True = False

|

-

If the parameter is ‘False’, return

‘True’. If the parameter is ‘True’,

return ‘False’.

-

Let’s try a more complex example:

|

nonzero :: Int -> Bool

nonzero 0 = False

nonzero _ = True

|

-

That underscore _ is a wildcard. Any value can go there, within reason. You use this when

you don’t really care what’s there.

-

Again, the order of the pattern matches matter, just like

guards.

|

(&&) :: Bool -> Bool -> Bool

True && b = b

False && _ = False

|

-

If I were to use the function like:

|

True && ((5 * 3 + 1) < (8 * 2 - 6))

|

-

The value of the expression on the right will be localised

within the variable ‘b’ in the code above.

-

With structure patterns, you can apply pattern matching with structures, like

lists or tuples.

-

For example, if you had:

-

This function foo, returns the first element of the input tuple: x.

-

The second element of the input tuple would be ignored, as

there is a wildcard there.

-

Another example:

-

As long as the first and third elements are ‘5’

and ‘4’, the result will be the second

element.

-

This also works with nested tuples and nested lists.

-

With list patterns, you can use the ‘cons’ operator with pattern

matching.

- For example:

-

If you did tail [1,2,3], then the variable ‘x’

would be ‘1’ and ‘xs’ would be

[2,3].

-

Basically, (x:xs) splits the list into its head and its

tail. Sometimes, this makes implementing recursive

algorithms easier. It also validates input to only lists

with at least one element.

-

If (x:xs) = [1,2,3] then x = 1, xs = [2,3]

-

If (x:xs) = [4] then x = 4, xs = [ ]

-

You can go further and add more, like:

|

addFirstTwoFromList (x:y:xs) = x + y

oneElementOnly

(x:[]) = True

|

-

With composite patterns, you can use all of the above together with multiple

arguments.

-

Here is an example of that:

|

fetch :: Int -> [a] -> a

fetch _ [] = error "Empty List"

fetch 0 (x:_) = x

fetch n (_:xs) = fetch

(n-1) xs

|

-

As you can see, pattern matching can be applied to any

parameter, and can be used as extensively as you need,

within reason.

-

String patterns are just normal patterns, but with strings.

-

Remember, they’re just lists of Chars. Therefore,

list patterns can be used with strings.

-

For example, ( _ : ‘a’ : _ ) matches strings

whose second character is ‘a’.

-

The pattern [] matches the empty string.

Lambda expressions

-

Lambda expressions are simple ways of creating quick functions without a

name.

-

For example, you could create an add function and apply it

like:

|

add :: Int -> Int -> Int

add x y = x + y

add 5 6

|

-

But did you know that you could also do:

|

(\x -> \y -> x + y) 5 6

or

(\x y -> x + y) 5 6

|

-

You don’t have to name it at all; you can just create

it quick, use it, and never refer to it again.

-

This is particularly useful when using functions like

‘map’.

Operator sections

-

An operator section is an infix operator in prefix

form:

-

Let’s say you wanted a function that just adds 5 to

stuff.

-

You could write:

|

add5 :: Int -> Int

add5 x = x + 5

|

-

But why write that when you can write:

-

This is because something like “5 + 4” can be

written as “(+) 5 4”.

-

So you can cut that expression in half and get just the

part where it adds 5: “(+5) 4” (because,

remember, everything is curried in Haskell).

-

It works both sides, so (+5) and (5+) are the same.

List Comprehension and Recursion

List comprehension

-

You can generate a list, a bit like set

comprehension.

-

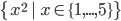

[x^2 | x <- [1..5]]

-

Those two expressions yield the same thing, except one is

set theory and one is Haskell.

-

[x^2 | x <- [1..5]]

-

The blue part is what will be in each element of the list.

-

The red part are the conditions that each element must abide

by.

-

You can even add more variables and conditions:

-

[(x,y) | x<- [1..5], y <- [6..10], x > y]

-

In general, list comprehensions look like this:

-

[exp | cond1, cond2, cond3, ..., condn]

Zips

-

There is a zip function, which lets you zip two lists

together into tuples.

- Example:

|

> zip ['a', 'b',

'c'] [1, 2, 3, 4]

[ ('a', 1), ('b', 2), ('c', 3) ]

|

STICKY FINGAAS!!!

-

This is pretty handy; you could use a list comprehension

over the zipped list.

-

For example, you could pair up elements of a list:

|

pairs :: [a] -> [ (a,a) ]

pairs xs =

zip xs (tail xs)

> pairs [1,2,3,4]

[(1,2),(2,3),(3,4)]

|

-

Then you could use a list comprehension to check if a list

is sorted:

|

sorted :: Ord a => [a] -> Bool

sorted xs = and [ x≤y | (x,y) <-

pairs xs ]

|

Recursion

-

Recursion is simple in Haskell.

-

Just refer to the same function again within the function

body:

|

fac 0 = 1

fac n = n * fac (n-1)

|

-

If you need to recurse through a data structure, like a

list, just do the following:

|

length :: [a] -> Int

length [] = 0

length (x:xs) = 1 + length xs

|

-

By doing this, ‘x’ is the first element of the

list and ‘xs’ is the rest of the list.

-

You can also use wildcards:

|

drop 0 xs = xs

drop _ [] = []

drop n

(_:xs) = drop (n-1) xs

|

-

You can also have mutual recursion, where two recursive

functions recurse each other!

|

evens :: [a] -> [a]

evens [] = []

evens (x:xs)

= x : odds xs

odds :: [a] -> [a]

odds [] = []

odds (x:xs) =

evens xs

|

-

These are the 5 steps to not lose marks in the exam better recursion:

-

Step 1: Define the Type

-

Step 2: Enumerate the Cases

-

Step 3: Define the simple (base) cases

-

Step 4: Define the other (inductive) cases

-

Step 5: Generalise and Simplify

Tail recursion

-

Tail recursion is a special kind of recursion that calls

itself at the end (the tail) of the function in which no

computation is done after the return of recursive

call.

-

In other words, the recursive calls do all the work, and at

the end, the answer is just returned, as opposed to normal

recursion, where a big computation is built up through

recursive calls, then at the end, the whole thing is

computed and returned.

-

Typically, tail recursion uses accumulators, whereas normal

recursion does not.

-

Here are two kinds of factorial function, one with tail

recursion and one without:

|

Tail recursion

|

No tail recursion

|

|

fac' :: Int -> Int -> Int

fac' acc 0 = acc

fac' acc n = fac'

(n*acc) (n-1)

fac' 1 5 -- Start

fac' 5 4

fac' 20 3

fac' 60 2

fac' 120 1

fac' 120 0

120

|

fac :: Int -> Int

fac 1 = 1

fac n = n * fac (n-1)

fac 5 -- Start

5 * fac 4

5 * 4 * fac 3

5 * 4 * 3 * fac 2

5 * 4 * 3 * 2 * fac 1

5 * 4 * 3 * 2 * 1

120

|

-

In the tail recursion version, all of the work is done in

the accumulator as each of the steps go by. Then, once the

base case is reached, the answer is simply spat out.

-

In the non-tail recursion version, no work is done by the

recursive steps; it’s just building up one big sum.

Once the base case is reached, one huge computation is

calculated and returned.

-

That’s the difference; tail recursion does stuff in

steps, whereas normal recursion does it in one huge chunk at

the end!

-

They still do the same thing, except tail recursion uses an

accumulator.

-

Sometimes, the tail recursion way is easier to

understand.

-

Because of the way Haskell works, these two methods work

exactly the same way, even under the hood!

-

That’s because Haskell is lazy, and won’t calculate things unless it really has to.

-

So Haskell won’t calculate the value of the

accumulator until the very end, which is what the non-tail

recursion method does.

Higher Order Functions

-

A higher order function is a function that either takes in

a function or returns a function.

-

The following are higher order functions:

|

func1 :: (a -> b) -> a

func2 :: a -> (b -> a)

|

Map, filter and fold

-

Why do we have higher order functions?

-

One of the reasons why is for the ‘map’

function.

-

The ‘map’ function allows you to apply a

function to all elements of a functor.

-

For example, you could use ‘map’ to add 5 to

all elements of a list:

|

map (\x -> x + 5) [1,2,3]

map (+5) [1,2,3]

-- result is [6,7,8]

|

-

Another example is ‘filter’, which allows you

to filter out things from a list:

|

filter (\x -> x == 5) [1,2,3,4,5]

filter (==5) [1,2,3,4,5]

-- result is [5]

|

-

Another example is ‘fold’. There are two fold

functions: ‘foldl’ and

‘foldr’.

-

‘foldl’ is left-associative, and

‘foldr’ is right-associative.

-

Here is an example that sums a list:

|

foldr (\x acc -> x + acc) 0 [1,2,3]

foldr (+) 0 [1,2,3]

|

-

The first argument is a lambda with an element and an

accumulator, the second argument is the starting value of

the accumulator and the third argument is the list to

fold.

-

‘foldl’ works pretty much the same way as

‘foldr’, except for the different associativity,

but there may be some efficiency gains. However, be wary of

infinite lists with ‘foldl’!

Dollar operator

-

The operator $ takes in a function and an argument and

applies the function to the argument.

-

Why not just run the function?

-

The reason why is $ associates to the right.

-

Here’s an example: let’s say you wanted to run

the following:

-

The answer you want is 5, but instead, you get 19.

Why?

-

Haskell is left-associative, so it does sqrt 3^2 first,

then adds it to 4^2.

-

To make it right, use this:

-

The $ operator associates to the right, so 3^2 + 4^2 will

be calculated first, then it’ll be

square-rooted.

Function composition

-

Another operator is the function composition (dot)

operator.

-

You can use it like maths, to join two functions

together.

-

So instead of

-

That’s basically English!

Declaring Types

Declaring Types and Classes

‘type’

-

You can define type synonyms, so that you can call a data

structure a name that makes more sense.

-

For example, we don’t say a character array (unless

you’re working with C), we say

‘string’.

-

We don’t use [Char], we use String.

-

Here is how you can define your own synonyms:

-

So now, instead of saying (Int, Int), you can say Pos

instead.

-

If you want to parameterise the class you want, you can do

that as well:

-

So now, when you do function type declarations, you can

feed in the class parameters of the synonym

‘Pair’, and those classes will be validated

inside the tuple.

- For example:

|

type Pair a b = (a, b)

f :: (Integral a, Integral b) => Pair a b -> Pair a b

f (x,y) = (x+1, y+1)

|

-

The function ‘f’ will only work if a pair of

integers are inputted, because it takes in “Pair

Integral Integral”.

-

Additionally, nesting types are allowed, but recursing them

is not.

|

type Pos = (Int,Int)

type Translation = Pos -> Pos -- Niiicee!!

type Tree = (Int, [Tree]) -- Ohh noo!!

|

‘data’

-

If you want to define a completely new type, and not just a

synonym, then you can use the ‘data’

keyword.

-

To instantiate a new type, you have to use it’s

constructor.

- Example:

|

data Pair = PairInt Int Int | PairString String String

|

-

To instantiate a new Pair, you need to use either the

constructor PairInt, or PairString, then the values. This

ensures type validation.

-

Here’s what’s allowed and not allowed with our

example:

|

-- RIGHT

PairInt 5 6

PairString "filthy acts" "at a reasonable price"

-- W R O N G

PairInt "killer queen" "bites the dust"

PairString 4 4

|

-

You can have lots of constructors separated by bars |.

-

Like type synonyms, data types can have parameters too,

like:

|

data Maybe a = Nothing | Just a

|

-

You can also do recursive types with

‘data’:

|

data BinaryTree a = Leaf a | Node a (BinaryTree a) (BinaryTree a)

Node 4 (Node 3 (Leaf 1) (Leaf 2)) Leaf 5 -- you could have this, for example

|

-

You can even do pattern matching:

|

getLeftBranch :: BinaryTree a -> BinaryTree a

getLeftBranch (Leaf a) = Leaf a

getLeftBranch (Node a x y) = x

|

‘newtype’

-

This is like a cross between ‘type’ and

‘data’. You can only have one constructor, and

you can only provide one type after a constructor.

- For example:

|

newtype Pair = Pair (Int, Int)

|

-

This means it’s more than just renaming something,

because you still need the constructor, but it’s more

restrictive than ‘data’ because you only have

one constructor and one type.

‘class’

-

You know how each class has their own function that applies

to every type that inherits that class?

- For example:

-

the class Eq has ==

-

the class Ord has < and >

-

the class Num has + and -

-

the class Functor has ‘map’ (more on that later!)

-

Let’s make our own, using the ‘class’

keyword!

- Example:

|

class Tree a where

flatten :: a b -> [b]

|

-

This is our ‘Tree’ class that represents trees.

It has a method ‘flatten’, which flattens all of

the values in the tree nodes.

-

The ‘a’ in ‘Tree a’ represents the

data structure that inherits the ‘Tree’ class,

for example ‘BinaryTree’.

-

The ‘b’ in ‘a b’ represents the

type of the node values in the data type

‘a’.

-

So now, we have our class, like Eq or Ord.

-

But Eq and Ord have their own instances, for example all

numbers inherit the class Eq or Ord. How do we create data

structures that inherit our class Tree?

‘instance’

-

We can use the ‘instance’ keyword to pair our

BinaryTree data type to our Tree class:

|

instance Tree BinaryTree where

flatten (Leaf v) = [v]

flatten (Node v x y) = [v] ++ flatten x ++ flatten

y

|

-

In our instance block, we have to define the functions

we’ve declared in the class block.

-

We need to define it in terms of BinaryTree, because

that’s what we’re making an instance of.

-

So ‘class’ defines what Tree does generally

with data type ‘a’, and ‘instance’

substitutes in ‘BinaryTree’ for ‘a’

and tells Haskell what to do if the program treats

BinaryTree like a Tree.

-

If that doesn’t make any sense, then go ahead and try

creating your own class with data types. You’ll learn

much better by doing, not reading!

Trees

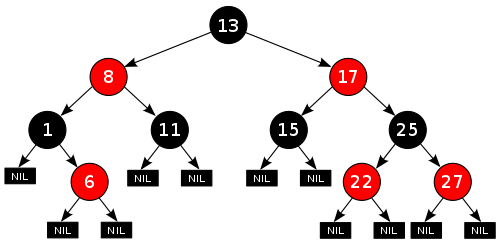

Red-Black Trees

-

Remember red-black trees from Algorithmics?

-

The root is black

-

All the leaves are black

-

If a node is red, it has black children

-

Every path from any node to a leaf contains the same number

of black nodes

-

Here is an example of a balanced red-black tree:

-

How do we do this in Haskell?

- Like this:

|

data RBTree a =

Leaf a

| RedNode a (RBTree a) (RBTree a)

| BlackNode a (RBTree a) (RBTree a)

|

-

We can also define a function called ‘blackH’

which finds the maximum number of black nodes from any

path - from the root to the leaf.

|

blackH (Leaf _ ) = 0

blackH (RedNode _ l r) = maxlr

where maxlr = max (blackH l) (blackH r)

blackH

(BlackNode _ l r) = 1 + maxlr

where maxlr = max (blackH l) (blackH r)

|

Abstract Syntax Trees

-

You can create a tree that represents syntax of an

algebra.

-

For example, you could do arithmetic:

|

data Expr = Val Int | Add Expr Expr | Sub Expr Expr

eval :: Expr -> Int

eval (Val n) = n

eval (Add e1 e2) = eval e1 + eval e2

eval

(Sub e1 e2) = eval e1 - eval e2

-- Example

eval (Add (Val 10) (Val 20)) -- Would return 30

eval (Sub (Val 20) (Val 5)) -- Would return 15

|

-

Even propositional logic:

|

-- Data type for propositional expression

data Prop = Const Bool

| Var Char

| Not Prop

| And Prop Prop

| Imply Prop Prop

-- Data type for a single pair of variable to

value

type Subst = [ (Char, Bool) ]

-- Takes a var, a substitution pair and returns

the value that the var is paired with

find :: Char -> Subst -> Bool

find k t = head [ v | (k',v) <- t,

k == k' ]

-- Evaluates a propositional expression

eval :: Subst -> Prop -> Bool

eval s (Const b) = b

eval s (Var c) = find c s

eval s (Not p) = not $ eval s p

eval s (And p q) = eval s p && eval s q

eval

s (Imply p q) = eval s p <= eval s q

-- Examples

eval [] (And (Const False) (Const True)) -- Would return False

eval [('a', True)] (Var 'a') -- Would return True

|

Functors

-

A functor is simply a class, like Ord or Num, that says

“this can be mapped over”.

-

For example, a list is a type of functor, because you can

use the “map” function on it.

-

The only function in this class is “fmap”.

“map” is the same as “fmap”, except

that it’s exclusively for lists.

-

Here is the class for Functor, as well as some

instances:

|

class Functor f where

fmap :: (a -> b) -> f a -> f b

instance Functor [] where

fmap = map

instance Functor Maybe where

fmap _ Nothing = Nothing

fmap g (Just x) = Just (g x)

|

-

When you create an instance of Functor in some class you

make, make sure it abides by the following laws:

|

fmap (g.h) = fmap g . fmap h

|

-

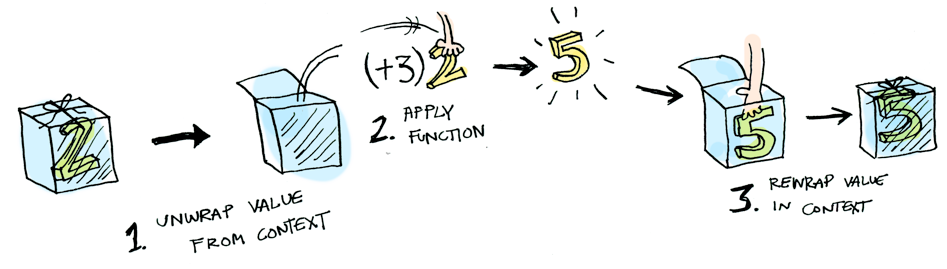

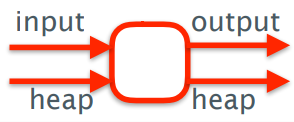

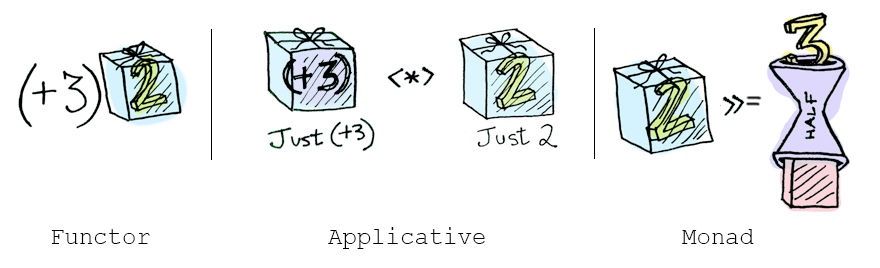

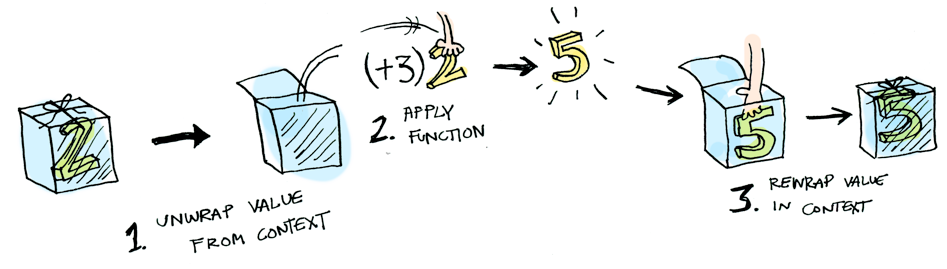

Here is an illustration of fmap (+3) (Just 2)

-

If you still don’t understand functors, I strongly

suggest this article about Functors, Applicatives and Monads. It has

really simple explanations and images to explain these

complex ideas!

-

A tree is also a type of data structure. We could create a

map function that works on trees, thereby making trees a

functor!

-

We could have something like:

|

instance Functor BinaryTree where

fmap g (Leaf v) = Leaf (g v)

fmap g (Node v x y) = Node (g v) (fmap g x) (fmap g

y)

|

-

Boom! Now we can use fmap on BinaryTrees if we wanted to,

like:

|

fmap (\x -> x + 10) (Node 5 (Leaf 3) (Leaf 6))

-- this will return: Node 15 (Leaf 13) (Leaf

16))

|

Directions, trails and zippers

-

We can define the direction in which we can traverse

through a tree, like this:

|

data Direction = L | R

type Directions = [ Direction ]

elemAt :: Directions -> Tree a -> a

elemAt _ (Leaf x) = x

elemAt (L:ds) (Node _ l _) = elemAt ds l

elemAt

(R:ds) (Node _ _ r) = elemAt ds r

elemAt

[] (Node x _ _) = x

-- Examples

elemAt [L] (Node 5 (Leaf 3) (Leaf 4)) -- returns 3

elemAt [R, L] (Node 5 (Leaf 6) (Node 2 (Leaf 8) (Leaf 9))) -- returns 8

|

-

How do we know how far we’ve gone?

-

We can build up a trail so we know the direction

we’ve gone in:

|

type Trail = [Direction]

goLeft :: (Tree a, Trail) -> (Tree a, Trail)

goLeft (Node _ l _ , ts) = (l , L:ts)

goRight :: (Tree a, Trail) -> (Tree a, Trail)

goRight (Node _ _ r , ts) = (r , R:ts)

-- Examples

(goLeft . goRight) (a, []) -- for some tree 'a', this will return

(b, [L, R]) where 'b' is the subtree if

you go right, then left in 'a'

|

-

You can also make a function to follow a trail, if you

like.

-

But what if you want to go back up? You don’t

remember the parent when you go left or right.

-

You can make it so that Direction stores the parent as

well:

|

data BinaryTree a = Leaf a | Node a (BinaryTree a) (BinaryTree a) deriving (Show)

data Direction a = L (BinaryTree a) | R (BinaryTree a) deriving (Show)

type Trail a = [ Direction a ]

parentInDirection (L p) = p

parentInDirection (R p) = p

goLeft :: (BinaryTree a, Trail a) -> (BinaryTree a, Trail a)

goLeft (Leaf x, ts)

= (Leaf x, ts)

goLeft ( p@(Node _ l _) , ts) = (l, (L p):ts)

goRight :: (BinaryTree a, Trail a) -> (BinaryTree a, Trail a)

goRight (Leaf x, ts)

= (Leaf x, ts)

goRight ( p@(Node _ _ r) , ts) = (r, (R p):ts)

goUp :: (BinaryTree a, Trail a) -> (BinaryTree a, Trail a)

goUp (tree, ts) = (parent,

restOfList)

where

latestMove = head ts

restOfList = tail ts

parent = parentInDirection

latestMove

-- Example

(goUp . goLeft) (tree, []) -- this will return (tree, []) because goLeft

followed by goUp effectively does nothing, like

taking a step forward then taking a step

back

|

ZIPPER MAN!

-

This concept of pairing one piece of data with another in a

list of pairs has a name in functional programming:

it’s called a zipper type.

Graphs

-

Functional programming is crap for modelling graphs.

-

Usually, if you wanted to work with graphs in a functional

programming paradigm, you’d use a hybrid language,

like JavaScript or F#.

-

In Haskell, we’ll look at three ways to try and model

graphs.

Indexed collections of Nodes, Edges

-

This is a nonstructural approach.

-

This is the easiest and most intuitive way to do

things.

-

Basically, you have a function that takes in a node and

returns a list of adjacent nodes, like so:

-

Actually, the lovely developers over at Haskell HQ has

already done this! In the Data.Graph package, they

have:

|

type Table a = Array Vertex a

type Graph = Table [ Vertex ]

|

-

Where ‘Vertex’ is some ID of the node, like an

Int or something.

-

They also provide functions for working with graphs, like

searching, building, fetching, reversing etc.

-

This is alright, but you can’t weight the edges and

the performance is slow.

Structured data type with cyclic dependencies

-

This has limitations for modifying the graphs.

-

It’s similar to the method from before, except

we’re not using an array; we’re using a cyclic

dependency.

-

What’s a cyclic dependency? Think of it like

this:

-

What is the value of xs = 0 : xs?

-

It’s an infinite string of zeroes: [0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0...]

-

Next: what is the value of xs where xs = 0 : ys, ys = 1 : xs?

-

This one’s a bit more tricky, but it’s [0,1,0,1,0,1,0,1...]

-

So you see, we’re defining these lists in a

“cyclic” manner, because they go back and forth,

around and around, like a circle.

-

What if we applied a cyclic dependency to our graph

structure?

-

First of all, to make it simpler, let’s assume that

each node only has one edge.

-

Let’s create a data structure for this:

|

data Graph a = GNode a (Graph a)

|

-

GNode a (Graph a)

-

The value of the node

-

Adjacent node; the node that this node can go to

-

Now, we want a function that converts a table of nodes to a

Graph structure:

|

mkGraph :: [ (a , Int) ] -> Graph a

|

-

Where our input table looks a little something like

this:

|

ID

|

Value

|

Next node

|

|

1

|

London

|

3

|

|

2

|

Berlin

|

4

|

|

3

|

Rome

|

2

|

|

4

|

Morioh

|

1

|

-

The implementation can go a little something like

this:

|

mkGraph :: [ (a, Int) ] -> Graph a

mkGraph table = table' !! 0

where table' =

map (\(x,n) -> GNode x (table'!!n) ) table

|

-

You can generalise this so that a node can have lots of

outgoing edges:

|

data GGraph a = GGNode a [GGraph a]

mkGGraph :: [ (a, [Int]) ] -> GGraph a

mkGGraph table = table' !! 0

where table' =

map (\(x,ns) -> GGNode x (map (table'!!) ns ) table

|

-

With this method, you don’t need to name nodes and

it’s fast to go from node to node. However, you

can’t build this structure incrementally; you have to

build it all at once.

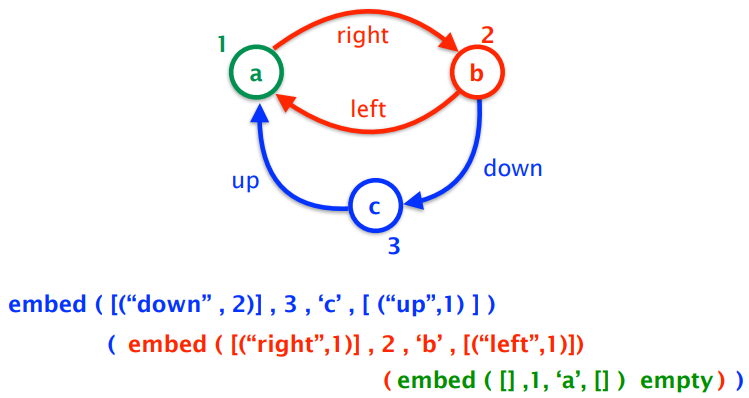

Inductive approach with graph constructors

-

This provides inductive structure and pattern

matching.

-

This is the library Data.Graph.Inductive.Graph.

-

Here, each node has an Int ID, like last time.

-

The graph is built one node at a time, and all the nodes

link together to form a graph, kind of like how you could

use a : b : c to form a list [a,b,c].

-

There are two key things to building a graph using this

approach:

|

empty :: Graph a b

embed :: Context a b -> Graph a b -> Graph a b

|

-

The ‘empty’ value is an empty graph with no

nodes or edges.

-

The ‘embed’ function embeds a new node into an

existing graph and returns the new graph.

-

So, what’s a context?

-

A context is a data structure that represents a node, on

its own, outside a graph.

-

It stores the node ID, the node label, the outgoing edges

and incoming edges.

|

type Adj b = [ (b,Node) ]

type Context a b = (Adj b , Node, a , Adj b)

|

-

type Adj b = [ (b,Node) ]

-

The label of the edge

-

The node on the end of this edge

-

type Context a b = (Adj b, Node, a, Adj b)

-

Incoming edges

-

Node ID of this node

-

Label of this node

-

Outgoing edges

-

An example of a graph with this is:

-

Of course, there are other ways to make this graph, which

will all work if implemented.

-

Not only can you build up a graph node by node, you can

decompose a graph node by node as well.

-

FGL provides a function ‘match’:

|

match :: Node -> Graph a b -> Decomp a b

|

-

Which takes in a node to remove, the graph itself, and

returns the graph without the node.

- Decomp is:

|

type Decomp a b = ( Maybe (Context a b), Graph a b )

|

-

the first element of the pair is either the removed node or

nothing.

-

the second element of the pair is the graph without the

node.

-

There’s also a function called matchAny:

|

matchAny :: Graph a b -> Decomp a b

|

-

If you don’t really care which node you take out;

it’ll remove any.

-

With these, you can create a map function for your

graph:

|

gmap :: (Context a b -> Context c b) -> Graph a b -> Graph c b

gmap f g

| isEmpty g = empty

| otherwise = embed (f c) (gmap f

g')

where (c, g') = matchAny g

|

Evaluation Order and Laziness

Equational reasoning

-

Equational reasoning simply means proving things by

following equations through.

-

For example, you could prove not (not False)) is False by simplifying it to not (True), then simplifying it further to False.

-

However, we’re going a little deeper by using proof

by induction.

-

Proof by induction:

-

To prove P(n) for all n, we prove P(0) and we then prove

for any k that P(k+1) holds under the assumption that P(k)

holds.

-

Say we had the natural number data type, like this:

|

data Nat = Zero | Succ Nat

|

-

Where 0 is Zero, 1 is Succ Zero, 2 is Succ Succ Zero

etc.

-

We also have an add function:

|

add :: Nat -> Nat -> Nat

add Zero m = m

add (Succ n) m = Succ (add n m)

|

-

How do we prove that ‘add’ is associative with

proof by induction?

-

We need to prove it for a base case and for an inductive

case.

-

We want to prove: add x (add y z) = add (add x y) z

|

Base Case

|

Inductive Case

|

|

add Zero (add y z) -- START

add (add Zero y) z -- GOAL

add Zero (add y z)

= { defn of add }

add y z

= { defn of add 'backwards'}

add (add Zero y) z

|

add (Succ x) (add y z) -- START

add ( (add (Succ x) y) z ) -- GOAL

add (Succ x) (add y z)

= { defn of add }

Succ (add x (add y z) )

= { inductive hypothesis }

Succ (add (add x y) z)

= { defn of add 'backwards'}

add (Succ (add x y) z )

= { defn of add 'backwards'}

add ( (add (Succ x) y) z )

|

-

You can even perform proofs on structures!

-

To see these proofs, look at the slides.

Redex

-

A redex, or “reducible expression”, is simply a

part of an expression that you need to know before you

compute the full expression.

-

For example, if you were to calculate the expression:

-

There are three redex’s inside this:

-

Because Haskell is fully functional, expressions like

“5 +” is actually a function, so to do, say,

“5 + 6”, Haskell finds the function “5

+”, then uses that function on “6”.

-

Therefore, even in an expression like “5 + 6”,

there is a redex “5 + 6” because Haskell needs to know that function

before computing the rest of the expression.

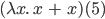

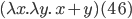

Beta-reduction

-

Beta reduction is a process that converts a function call

into an expression.

-

You’re familiar with lambda expression, right? You

should be; I covered it a few sections ago.

-

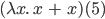

If not, it goes like this:

, where the first ‘x’ after the lambda is the

parameter and everything after the dot is the function body.

The syntax can vary, but that’s the gist of it.

, where the first ‘x’ after the lambda is the

parameter and everything after the dot is the function body.

The syntax can vary, but that’s the gist of it.

-

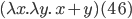

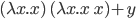

You can call a lambda function like this:

, which is

, which is  .

.

-

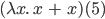

If you wanted multiple parameters, you would do

, which is

, which is  (it’s similar to how Haskell curries

everything).

(it’s similar to how Haskell curries

everything).

-

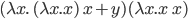

When we converted

to

to  , we’ve done beta reduction.

, we’ve done beta reduction.

-

More generally, if we had a function

and an input

and an input  , to beta reduce, just take the function body and replace

all

, to beta reduce, just take the function body and replace

all  with

with  .

.

-

Just like in our example, we took the function body

and replaced all

and replaced all  with

with  .

.

-

Here’s a more complex example: how do we

reduce...

-

...using beta reduction?

-

This is a big jump, but if we break this up and do this

step-by-step, it’s not so bad.

-

First of all, let’s isolate the function body:

-

Now let’s split this up into its terms:

-

Our argument is

. Which of those terms are

. Which of those terms are  ?

?

-

Just the one, right? So we replace that:

-

Now we work back into the function body...

Call-By-Name

-

Outermost reduction with no reduction under lambda is more

commonly known as call-by-name reduction. This is used by Haskell.

-

In layman’s terms, this means that function calls are

processed without processing or even looking at the

arguments.

-

For example, let’s say we have an infinite list, and

we want to get the first element of that infinite

list:

-

Call-by-name doesn’t care about the infinite list; it

won’t try to process it. Instead, it’ll just

perform the function “take 1” and take 1 element

off of that list. The result will simply be [1].

-

Because of this, Haskell can efficiently process

information by lazy evaluation.

-

Haskell also uses something called graph reduction to perform lazy evaluation.

-

Remember in beta-reduction where an expression is repeated

wherever the function parameter is?

-

With graph reduction, only one instance of the expression

is stored and multiple pointers to that expression are used

instead.

-

Therefore, any reductions performed on the single copy will

permeate throughout all references of that expression.

-

You want an example of graph reduction? Alright: consider

this Haskell line:

-

With call-by-name, we don’t care what that argument

is. We just create a list of 10 unevaluated expressions of

. But since they’re all unevaluated, if we tried to

display this list, wouldn’t we have to calculate

. But since they’re all unevaluated, if we tried to

display this list, wouldn’t we have to calculate  10 times for each element?

10 times for each element?

-

You are wrong! Remember, Haskell uses graph reduction.

There is only one

; every element in that list is a pointer to that one

; every element in that list is a pointer to that one  . Therefore, we only need to calculate

. Therefore, we only need to calculate  once, then all the pointers will update.

once, then all the pointers will update.

Call-By-Value

-

Innermost reduction with no reduction under lambda is more

commonly known as call-by-value reduction. This is used by languages like C++, Java, Python etc.

-

In English, this means that arguments are processed before

the function is called.

-

For example, let’s say we have an infinite list, and

we want to get the first element of that infinite

list:

-

Call-by-value will try and process that infinite list, and

it’ll be there forever because there’s no end to

it. Therefore, this function call will not end.

Modularity

-

Let’s just say we want a Haskell program that yields

us a list of 300 1’s. Here’s two different

possible solutions:

|

Solution A (the good one)

|

Solution B (the crap one)

|

|

ones = 1 : ones

take 0 _ = []

take _ [] = []

take n

(x:xs) =

x : take (n-1) xs

take 300 ones

|

replicate 0 _ = []

replicate n x =

x : replicate (n-1) x

replicate 300 1

|

-

Solution A splits the code into data (ones) and control

(take).

-

Solution B blends the two together.

-

Solution A is better because it’s more modulated,

therefore:

-

it’s easier to debug

-

parts of it are reusable

-

easier to read and understand

-

you split the problem up into subproblems, making it easier

to program

-

The point is, Haskell allows modularity through

laziness.

-

You can use this for other examples too, like creating a

list of all prime numbers using the Sieve of Eratosthenes

(data), then taking the first 100 primes (control).

Strict application

-

If you wanted to, you could scrap all of this and use

strict application.

-

Basically, it tells Haskell to evaluate the expression on

the right before applying the function. It’s used with

the ‘$!’ operator.

-

It’s mainly used for space efficiency, and it allows

for true tail recursion.

- Example:

|

Step

|

Code

|

|

1

|

square $! (1 + 2)

|

|

2

|

square $! (3)

|

|

3

|

square 3

|

|

4

|

9

|

Interpreters and Closures

Part 1 - Substitutions

-

We’re going to write an interpreter in Haskell!

-

What language should we interpret?

-

How about lambda calculus? The rules are pretty simple

there.

Lambda calculus

-

What is lambda calculus?

-

It’s a formal system to express functions.

-

There are only three rules: variables on their own,

function application and function abstraction.

-

Here they are:

|

Rule

|

Description

|

Format

|

Example

|

|

Variable

|

It’s just a variable on it’s

own.

|

Just some symbol on it’s own

x

|

x

y

|

|

Function abstraction

|

A function definition

|

A lambda character, followed by a variable

name, followed by a full stop, followed by the

function body which is another lambda

expression

λ(some variable).(some lambda

expression)

They can be curried to have more

parameters

λ(some

variable).λ(anothervariable).λ(yet

another variable) … .(some lambda

expression)

Instead of dots, you can use an arrow, if you

wish

|

λx.x

λx.λy.y

λx.λx.x

λx.λy.λz.y

OR

λx→x

λx→λy→y

λx→λx→x

λx→λy→λz→y

|

|

Function application

|

A function being applied to some

expression

|

It’s just an expression separated by an

expression with a space

(a lambda expression) (another lambda

expression)

It represents calling a function with some

input

|

λx.x x

λx.λy.y y

x y

λx.λy.y

λy.λy.y

|

-

Despite how simple it is, it can encode a lot of

information.

-

It can encode arithmetic, logic, structured data etc.

-

A variable x is bound in the term λx → e and the scope of the binding is the expression e.

-

A variable y is free in the term λx → y because it was initialised outside of the scope of

this function abstraction.

-

A lambda expression with no free variables is called closed.

Beta reduction syntax

-

Remember beta reduction a few sections ago?

-

If not, scroll up and read it. It’s literally right

above this section.

-

We’re going to express beta reduction like

this:

-

(λx → e1) e2

-

will be rewritten as

-

e1 [ x := e2 ]

-

Read it like “In e1, replace all x with e2”.

Alpha conversion

-

(λx → (λy → x)) y

-

which is basically

-

(λy → x) [ x := y ]

-

which becomes

-

(λy → y)

-

Everything seems fine and dandy.

-

But what if we have this:

-

λy → ((λx → (λy → x))

y)

-

it will become

-

λy → (λy → y)

-

Ah... that’s not exactly what we wanted. That y is

now bound by the inner function, not the outer function like

it’s supposed to.

-

If only we could rename the parameter of the inner

function...

-

What? That’s already a thing?

-

Alpha conversion renames an inner function so that you

don’t get variable capture, which is a phenomenon that occurs in substitution when a

free variable becomes bound by the term you substitute it

into.

-

So if we rename the inner y to z, we can have:

-

λy → ((λx → (λz → x))

y)

-

it will become

-

λy → (λz → y)

-

Everything is fixed thanks to alpha-conversion!

-

With all of these rules, you can now build your

interpreter!

-

If you really want to know how, look at these slides.

Part 2 - Machines

-

Plot twist! Part 1 is a load of crap and you

shouldn’t implement interpreters that way.

-

Well, you can, but it’s really inefficient.

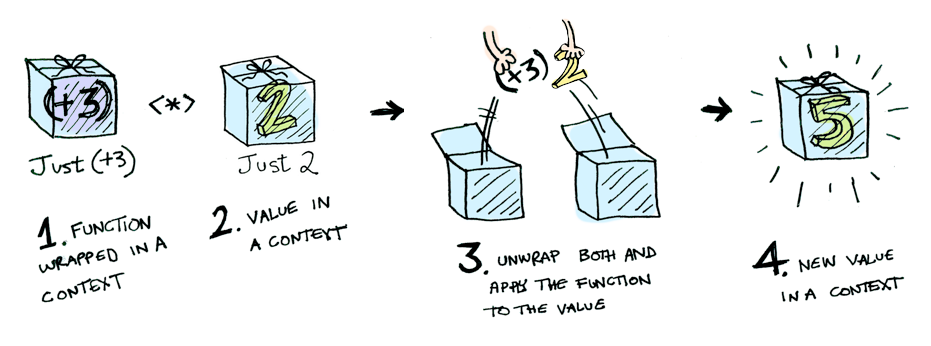

Environments

-

We have this lambda expression:

-

(λx -> x) e

-

With normal beta reduction, this becomes just

- e

-

But what if we were lazy and just said

-

x (but we know that e is substituted as x)

-

We’re not explicitly replacing anything, we’re

just storing a record of the substitutions.

-

Therefore, we could look up stuff when we need it.

-

This is the concept of an environment.

-

An environment records bindings of variables to

expressions, just like a mapping.

-

For example, if we had the expression

-

(λx -> e1) e2

-

... and we wanted to use beta reduction with environments,

we could go about this like:

|

|

Expression

|

Environment

|

|

Before beta reduction

|

(λx -> e1) e2

|

Nothing

|

|

After beta reduction

|

e1

|

x is mapped to e2

|

-

How do we write this in proper syntax?

-

We’ll write

-

e | E

-

to represent an expression e in the environment E.

-

So now, our beta reduction looks like:

-

(λx -> e1) e2 | E ⟼ e1 | E [ x := e2 ]

-

Where E [x := e2] means environment E updated with the new binding of x to the expression e2.

-

Note that e1 may now contain free occurrences of x.

-

That means we should have a rule like:

-

x | E ⟼ “lookup x in E” | E

-

... so that we can look up free occurrences of x when we get to them.

Frames

-

Another improvement to our interpreter is to make it so

that it only focuses on the subterm that needs evaluating

next.

-

Keep in mind that everything that follows is tailored to a call-by-value strategy.

-

Have a think about what we actually do when we look at an

expression:

|

Expression

|

What do we do?

|

|

x

|

It’s just a variable. We can’t

simplify this down any further, so just leave

it. It’s terminated.

|

|

λx -> e

|

This is just a lambda term on it’s own.

We can’t simplify this any further, so

leave it. It’s terminated.

|

|

(λx -> e1) e2

|

This is an application, which can be reduced.

First of all, we reduce e2, then we perform beta

reduction.

|

|

e1 e2

|

We can simplify this, also. If we’re

doing left-most, we simplify e1 then e2, and if

we’re doing right-most, we simplify e2 and

then e1.

We will be doing left-most for now.

|

-

So there’s two possibilities of simplifying things

down: either we have a lambda application, or a normal

application with two expressions.

-

When we simplify the lambda application, we take out the e2

and leave the rest, leaving just

-

(λx -> e1) [-]

-

Where [-] is a hole or an empty void where we took out e2 and

can plug in other expressions.

-

Once we’ve simplified e2, we plug it back in and we

perform beta reduction.

-

When we simplify the application, we take out e1, leaving

just

-

[-] e2

-

Once we’ve simplified e1, we plug it back in and take

out e2, leaving:

-

e1 [-]

-

Once we’ve simplified e2, we plug that back in and we

can continue.

-

All of these expressions with [-] in them are called frames.

-

They’re sort of like a “snapshot” of what

we haven’t evaluated yet as we venture deeper into the

lambda expression.

-

Think of it like a Java call stack, how

‘frames’ are stacked when you call lots of

methods.

-

A stack of frames is called a continuation.

-

Just for reference’s sake, a value is a terminated expression; one that cannot simplify

anymore.

Continuations

-

Now that we have continuations, let’s rewrite our

reductions as follows:

-

e | E | K ⟼ e’ | E’ | K’

-

Where K is our continuation.

-

When do we push a new frame onto the stack?

-

We push when we have an unevaluated expression that we want

to simplify.

-

e1 e2 | E | K ⟼ e1 | E | ([-] e2) :: K

-

When do we pop a new frame off the stack?

-

If our focussed expression is terminated (which will be

represented with a V), there’s three

possibilities:

-

K is empty

-

We’re finished; the evaluation has terminated

-

We now need to take out e2 and put back e1 (now called V

because we should have simplified it), by popping the e2

frame and pushing a new frame with V on it:

-

V | E | [-] e2 :: K ⟼ e2 | E | V [-] :: K

-

K has (λx -> e1) [-] at the top

-

We need to perform beta reduction:

-

V | E | (λ x -> e) [-] :: K ⟼ e | E [x := V] | K

CEK-machines

-

Let’s combine these three ideas into one set of

rules.

-

This is called a CEK-Machine, and it stands for:

-

Control

-

Environment

-

Kontinuation

-

Each of these make up the syntax we’ve been using all

this time:

-

Here’s the rules, in all their glory:

|

#

|

C

|

E

|

K

|

C

|

E

|

K

|

|

1

|

x

|

E

|

K

|

“lookup x in E”

|

E

|

K

|

|

2

|

e1 e2

|

E

|

K

|

e1

|

E

|

[-] e2 :: K

|

|

3

|

V

|

E

|

[-] e :: K

|

e

|

E

|

V [-] :: K

|

|

4

|

V

|

E

|

(λx -> e) [-] :: K

|

e

|

E [x := V]

|

k

|

R1: x | E | K

⟼ “lookup x in E” | E

| K

R2: e1 e2 | E | K

⟼ e1 | E

| [-] e2 :: K

R3: V | E | [-] e :: K ⟼ e | E

| V [-] :: K

R4: V | E | (λx -> e) [-] :: K ⟼ e | E [x := V]

| K

|

Rule #

|

Explanation

|

|

1

|

If we see a single variable on it’s own,

look it up in the environment and replace it

with that corresponding expression.

|

|

2

|

If we see an application, take out the left

expression for simplifying and put the right

expression onto the stack.

|

|

3

|

If we have a fully simplified expression and

there’s an application on the stack that

has a left-side missing, put the left side back

and take out the right-side for

simplifying.

|

|

4

|

If we have a fully simplified expression and

there’s a lambda application on the stack

that has a right-side missing, perform beta

reduction on our terminated value and that

function application.

|

-

But not too much glory! There’s a problem.

Closures

-

What’s the problem?

-

Have a look at this expression:

-

(λz -> λx -> (λy -> y z x y)

(λx -> z x)) e1 e2

-

This looks daunting at first, but let me split this up for

you:

-

(λz -> λx -> (λy -> y z x) (λx -> z x)) e1 e2

-

Remember that z is e1 and x is e2.

-

Now, I want you to focus on this part here:

-

λy -> y z x

-