Algorithmic Game Theory Appendix

Matthew Barnes

Gale-Shapley Algorithm Example 2

Irving’s Algorithm Phase 1 Example 8

Irving’s Algorithm Phase 2 Example 11

Random Serial Dictatorship Example 18

Simultaneous Eating Algorithm Example 21

Impossibility of DS Truthfulness Proof for SM 26

Extensions of Stable Roommate (SR) 28

Secretary Problem with Dynamic Programming 32

Factor-revealing LP Algorithm 41

Does a fair allocation always exist? 48

|

|

Behold! Our example of matching lecturers (leaders) to ANAC winners (followers).

Let me introduce you to:

Everyone’s preferences are listed beneath them. |

|

|

This is a leader-oriented example, so the leaders propose.

We’ll start with the top-most leader, Enrico. His first choice of follower is AgentHerb, so Enrico will propose to AgentHerb. |

|

|

AgentHerb doesn’t have any pairing yet, so AgentHerb accepts Enrico’s proposition and pairs with Enrico!

Now, Enrico scratches AgentHerb from his list and AgentHerb scratches Enrico off their list.

We move on to the next leader: Bahar. Her first choice of follower is AgentGG, so she proposes to them. |

|

|

AgentHerb also doesn’t have a pairing, so AgentHerb forms a matching with Bahar and they scratch each other off their lists.

Lastly, we move on to Jie. His first choice of follower is also AgentGG, so he proposes to them. |

|

|

Awkward 😳 AgentGG actually prefers Jie to Bahar, but AgentGG is already matched with Bahar. What is an ANAC winner to do?

In this case, AgentGG breaks up with Bahar and instead forms a match with Jie (and scratches the other off their lists). Poor Bahar! I suppose this is payback for outbidding Jie on that Greggs veggie bake?

In any case, Bahar now doesn’t have a matching; she is free. |

|

|

Bahar, now being the only one without a matching, gets to go next. The next follower on her list is AgentHerb, so she proposes to them. |

|

|

Oh no! When will the tragedy end?

AgentHerb preferred Bahar to Enrico, so they split up with Enrico and matched with Bahar! Now Enrico is the ‘free’ one! |

|

|

Enrico proposes to the next follower in his list, AgentGG.

Unfortunately, AgentGG prefers their own matching, Jie, to Enrico, so no dice. |

|

|

Enrico proposes to the last follower on his list, ParsCat2.

ParsCat2, being the lonely, unwanted cat that they are, has no matching currently, so they accept Enrico’s proposal.

Now we have a stable matching!

If you ask me, I don’t know why everyone preferred ParsCat2 last. I’d like a robot cat. |

|

|

We have 6 residents, and 3 hospitals. Each resident gives preferences for two hospitals they like, and the hospitals give preferences for the residents they like. |

|

|

First, r1 applies to h2, and a match is made.

h2 isn’t over-subscribed or full, so we move on. |

|

|

r2 applies to h1, and a match is made. Again, h1 isn’t over-subscribed or full, so we move on. |

|

|

r3 applies to h1, and a match is made. Now, h1 is full, so h1 scratches off all residents on their list that are less desirable than the assigned r3 and r2, and h1 is also removed from r5 and r6’s lists.

|

|

|

r4 applies to h2, and a match is made. h2 is now full, so the residents less desirable than r1 and r4 are scratched off (r5), and h2 is removed from r5’s list.

r5 no longer has any hospitals on their list! r5 will not have any matchings. |

|

|

r6 applies to h2, who is over-subscribed. Therefore, the worst resident on h2’s list is scratched off and replaced with r6.

r4, now without a hospital, has their turn next. |

|

|

r4 applies to the next hospital on their list, h3. They have no residents, so h3 accepts r4. h3 isn’t full or over-subscribed, so that’s the end of that.

Now, all residents are either allocated or have no hospitals left to apply to! This is our resident-optimal stable matching. |

|

|

We have the same setting as the previous example. |

|

|

First, we start with h1. It has two available seats, so we look at the first two residents in our preference list, r1 and r3.

They’re both free, so we assign r1 and r3 with h1.

r1 and r3 are now no longer free. This means we need to scratch off the hospitals they prefer less than h1.

r1 doesn’t have any hospitals they like less than h1, but r3 does: h3. So h3 is scratched off r3’s list, and vice versa on h3’s list. |

|

|

h2 also has two available seats, so we look at the first two residents of h2’s preference list, r2 and r6.

They’re also both free, so we assign r2 and r6 to h2.

r2 and r6 are no longer free, but they don’t have any hospitals they desire less to scratch off. |

|

|

h3 has two available seats, but only one (available) resident on their list, so they can only propose to r4.

r4, being free, accepts h3 and makes a matching.

There we have it! All hospitals are now fully subscribed, or have no more residents to propose to. This is our hospital-optimal stable matching. |

|

|

We have the same setting as the previous example. |

|

|

Let’s start at the top, with A.

A proposes to C, and a matching is made.

Now, we go through the successors of A on C’s list (which is just F), and we remove the matching (C,F). |

|

|

Now, B proposes to F, and a matching is made between B and F. |

|

|

This could go on for a while, so let’s speed this up:

|

|

|

Now, E tries to propose to C. C actually prefers E to A, so C lets E semi-engage with them, and ditches A!

A is no longer semi-engaged with anyone. |

|

|

Let’s try and find someone for A again.

A proposes to D, and accepts; now A is semi-engaged to D. |

|

|

Lastly, F proposes to A, and A accepts. E is a successor to F in A’s list, so (A,E) is removed.

All the crossed out agents are simply removed in the picture. |

|

|

|

I am once again using examples from the slides, because sod making my own ones.

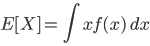

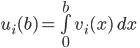

Let

Let

Let

Let

The image above is everyone’s preferences.

The priority order is as follows:

|

|

|

|

We start with our first student: a13!

According to the preferences, a13 likes h6, hence the arrow from a13 to h6.

However, we can’t give h6 to a13, because it’s already owned by a6. What are we to do?

Remember the name of the algorithm? “You Request My House, I Get Your Turn”? a6 gets a13’s turn! By that, I mean we put a6 to the front of the priority list and continue, hence the blue arrow from a6 to the start. |

|

|

|

Now, a6 is at the start, so we take a6’s turn.

a6 likes h6, giving us a cycle: h6 → a6 → h6 → ...

When we have a cycle, we do the same thing that we do in TTC: assign each agent the house they’re pointing at in the cycle. So, we give h6 to a6. |

|

|

|

Now that h6 is gone, a13 can’t point to it anymore.

So, we make a13 point to its next favourite house: h13.

Nobody owns h13, so a13 is free to claim it: we allocate a13 with h13.

a13 → h13 |

|

|

|

Next is a15. They like h1, but a1 already owns it, so a1 takes a15’s turn and goes to the front of the priority list. |

|

|

|

Now it’s a1’s turn. a1 actually likes a completely different house: h15.

Nobody owns that, so a1 is free to take it. Since h1 will be free after a1 moves out, a15 is free to take h1!

Effectively, we’re giving the students what they’re pointing towards. It works like a chain, you see? Or one of those cycles, but without the... cycle.

a1 → h15 a15 → h1 |

|

|

|

Now, it’s a11’s turn. a11 likes h2, which a2 owns, so a2 is put to the front of the priority list. |

|

|

|

a2’s turn is next, and they like h3. a3 already owns that, so a3 is put to the priority list. This ‘combo’ is getting bigger! |

|

|

|

a3 actually likes their own home, h3. That creates a cycle: h3 → a3 → h3 → ..., so a3 gets to keep h3. |

|

|

|

a2 can’t point to h3 anymore, so it must point to its next favourite: h4. But that’s already owned by a4, who takes a2’s turn! Can’t a2 ever catch a break? |

|

|

|

a4, surprisingly, likes h2. Now we have a proper cycle!

h2 → a2 → h4 → a4 → h2 → ...

So, we can make the following assignments:

a2 → h4 a4 → h2 |

|

|

|

a11 can’t point to h2 anymore, so they point to their next favourite, h16. Nobody owns that, so a11 is free to take it.

a11 → h16 |

|

|

|

a14, who is next, likes h8. That’s owned by a8, so they go in front. |

|

|

|

a8 likes h12, which is free, so they get it. Now that h8is free, a14 can get h8. This is just like that chain from earlier.

a8 → h12 a14 → h8 |

|

|

|

a12 likes h14, which is free, so they can just take it.

a12 → h14 |

|

|

|

a16 likes h5, which is owned by a5, so a5 goes to the front of the priority list. |

|

|

|

a5 likes h9, which is owned by a9, so a9 now goes to the front of the priority list. |

|

|

|

a9 actually likes h11, which is free. That’s a big chain! All students get the houses they point at.

a9 → h11 a5 → h9 a16 → h5 |

|

|

|

Almost there! a10 likes h7, which is owned by a7, so a7 goes in-front of a10. |

|

|

|

a7 actually likes their own home, forming a small cycle, so a7 gets to keep h7.

a7 → h7 |

|

|

|

Come on. Do you really need an explanation for

this? a10 → h10 |

|

|

|

Here’s the outcome of the algorithm! Phew... that took a while.

It should be called “You Waste Your Time, You Get The Same Thing As TTC”. |

|

|

Since this is the teachers allocation problem, why don’t we use the lecturers for this example?

Enrico, Bahar, and Jie need to split the teaching load of their new module, Advanced Advanced Intelligent Agents, a.k.a Advanced Game Theory.

They need to decide who teaches Nash Equilibria, Prisoners Dilemma, and Auctions.

In Random Serial Dictatorship, we’d scramble the order of the lecturers, but for simplicity’s sake we’ll just use this order. |

|

|

First up is Enrico! His first choice is Prisoner’s Dilemma, so he is assigned to that.

It’s scratched off everyone’s list, so nobody else can claim it. |

|

|

Next is Bahar! She can’t pick her favourite, Prisoner’s Dilemma, because it’s taken by Enrico.

So, she’ll have to pick her next best, which is free: Nash Equilibria. |

|

|

Lastly, it’s Jie! He’d like Nash Equilibria, but it’s taken by Bahar. Next, he’d like Prisoner’s Dilemma, but that’s taken by Enrico.

The only thing he can take is Auctions, so Jie is assigned to Auctions.

That concludes this algorithm! |

different orderings.

different orderings.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Enrico, Bahar, Jie

|

Enrico, Jie, Bahar

|

Bahar, Enrico, Jie

|

|

4 |

5 |

6 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Bahar, Jie, Enrico

|

Jie, Enrico, Bahar

|

Jie, Bahar, Enrico

|

|

|

s1 |

s2 |

s3 |

|

t1 |

1/6 |

4/6 |

1/6 |

|

t2 |

1/6 |

2/6 |

3/6 |

|

t3 |

4/6 |

0/6 |

2/6 |

|

|

|

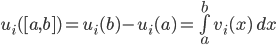

Please welcome back our esteemed guests: Enrico, Bahar, and Jie, for their participation in this Simultaneous Eating Algorithm example.

The flight here was a long one, and now they’re hungry hungry! Luckily, we have some food for them. We have a Greggs veggie bake, a grilled cheese sandwich, and some onigiri (not jelly-filled doughnuts).

Everyone has preferences over these lovely dishes, and we want to split them up between everyone. We do this through an ‘eating’ algorithm. The proportion of food items everyone manages to eat is their allocation.

A few things before we start:

What are you all waiting for? Tuck in! |

|

|

|

In this algorithm, everybody starts eating their favourite foods first. This means Enrico and Bahar start with the veggie bake, and Jie starts with the grilled cheese sandwich.

Time goes on, until Enrico and Bahar finish their veggie bake. Since they were both eating the same one (and, as I said before, everyone eats at the same rate), they both ate half each. That means Enrico is allocated 0.5 of the veggie bake, and Bahar is also allocated 0.5 of the veggie bake.

Jie is not done yet. He’s only eaten 0.5 of the sandwich, so he’s allocated 0.5 of the sandwich so far, but that may increase.

Since Enrico and Bahar are finished, they’ll move on to their next favourite food. Enrico will start eating the sandwich with Jie, and Bahar will start eating the onigiri on her own. |

|

|

|

Before Enrico started eating the sandwich, Jie had already eaten 0.5 of it. That means Enrico and Jie had to share the other half of the sandwich between themselves. Because of this, it took Jie and Enrico 0.25 time units to eat the rest of the sandwich. This means Enrico is allocated 0.25 for the sandwich, because he only managed to eat 25% of the whole thing, and Jie is allocated 0.75 for the sandwich, because he ate the first half (0.5) and the other 0.25 alongside Enrico.

While all of this is happening, Bahar is still happily eating her onigiri, and has gotten through 0.25 of it.

Enrico is now finished, so he’ll start eating the last item on his list: the onigiri. Jie will do the same, since Enrico and Bahar already polished off the veggie bake from before. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Before everyone started eating the onigiri, Bahar had already eaten 0.25 of it. So, that leaves 0.75 of the onigiri to pass around now. There’s three people eating it now, so everyone evenly eats 0.75 / 3 = 0.25 onigiri.

Bahar is allocated 0.5 onigiri, because she ate 0.25 before and 0.25 now. Enrico and Jie are allocated 0.25 onigiri, because they ate 0.25 while sharing with everyone.

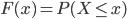

The final allocations are as follows:

|

is

is  as well?

as well?

:

:

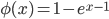

that, given a possible minimum value, returns the relative likelihood that two valuations drawn will have that minimum

value.

that, given a possible minimum value, returns the relative likelihood that two valuations drawn will have that minimum

value.

.

.

that, given a possible minimum value, returns the

probability that a randomly drawn pair of valuations will have that minimum value or lower.

that, given a possible minimum value, returns the

probability that a randomly drawn pair of valuations will have that minimum value or lower.

is, that’s a minimum value gotten from drawing

two random valuations. This

is, that’s a minimum value gotten from drawing

two random valuations. This  represents the probability that a minimum value

gotten from two random valuations is less than or equal to

our given value

represents the probability that a minimum value

gotten from two random valuations is less than or equal to

our given value  .

.

|

|

and

and  are drawn independently, we can split them up

here:

are drawn independently, we can split them up

here:

|

|

and

and  are drawn in the exact same range with the same

distribution, these two probabilities here are actually the

same, so let’s collect them:

are drawn in the exact same range with the same

distribution, these two probabilities here are actually the

same, so let’s collect them:

|

|

and

and  are uniformly distributed on

are uniformly distributed on  , so we can rewrite this function as:

, so we can rewrite this function as:

|

|

|

if |

|

|

|

if |

|

|

1 |

if |

|

|

|

if |

|

|

|

otherwise |

|

|

|

|

.

.

and

and  .

.

or

or  .

.

.

.

declares that she prefers

declares that she prefers  instead of

instead of  , the mechanism will now only pick

, the mechanism will now only pick  .

.

will get matched with

will get matched with  instead of

instead of  and get a better matching!

and get a better matching!

.

.

declares that she prefers

declares that she prefers  instead of

instead of  , the mechanism will now only pick

, the mechanism will now only pick  .

.

will get matched with

will get matched with  instead of

instead of  and get a better matching!

and get a better matching!

?

?

, preference list is empty in the phase-1 table,

then:

, preference list is empty in the phase-1 table,

then:

cannot be matched in any stable matching

cannot be matched in any stable matching

is unmatched

is unmatched

.

.

|

Theorem (Ronn, 1990) |

|

Deciding whether a stable matching exists, given an instance of SRT, is NP-complete. |

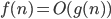

and

and  ,

,  if there are positive constants

if there are positive constants  and

and  such that

such that  for all

for all  .

.

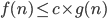

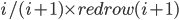

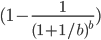

has a performance guarantee

has a performance guarantee  , for some

, for some  , if:

, if:

for any instance

for any instance  for minimisation problems, and

for minimisation problems, and

for any instance

for any instance  for maximisation problems.

for maximisation problems.

is the measure of an optimal solution, and

is the measure of an optimal solution, and  is the size of the solution produced by

is the size of the solution produced by  .

.

unless P = NP

unless P = NP

assuming the Unique Games Conjecture.

assuming the Unique Games Conjecture.

though, which is what Kiraly’s 3/2 approximation algorithm does.

though, which is what Kiraly’s 3/2 approximation algorithm does.

|

Summary of Kiraly’s algorithm |

|

When a man is rejected by all women in his list, he is given a second chance and can propose to women on his list again one more time.

Preferences

Proposals and rejections

For an example of this algorithm, see the slides. |

, for any

, for any  , unless P = NP.

, unless P = NP.

.

.

Y, Y mechanisms are not DS truthful:

Y, Y mechanisms are not DS truthful:

.

.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

to

to  .

.

is the best out of everyone, assuming they’re

better than everyone before them, is

is the best out of everyone, assuming they’re

better than everyone before them, is  .

.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.125 |

0.25 |

0.375 |

0.5 |

0.625 |

0.75 |

0.875 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.

.

, it’s obvious that the probability of finding the

best candidate when skipping

, it’s obvious that the probability of finding the

best candidate when skipping  should be 0, because if we skip the last candidate,

we won’t get a candidate.

should be 0, because if we skip the last candidate,

we won’t get a candidate.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

0.125 |

0.25 |

0.375 |

0.5 |

0.625 |

0.75 |

0.875 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

|

0.410 |

0.410 |

0.410 |

0.380 |

0.318 |

0.232 |

0.125 |

0 |

|

0.125 |

0.25 |

0.375 |

0.5 |

0.625 |

0.75 |

0.875 |

1 |

|

0.410 |

0.410 |

0.410 |

0.5 |

0.625 |

0.75 |

0.875 |

1 |

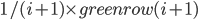

, the green row picks the red values.

, the green row picks the red values.

lies!

lies!

to

to  .

.

is 3.

is 3.

|

$ python secretary.py [N] |

exponential time complexity without DP.

exponential time complexity without DP.

pattern).

pattern).

time complexity for this one sub-tree of optimal_k_with_i.

time complexity for this one sub-tree of optimal_k_with_i.

, which can be simplified to

, which can be simplified to  .

.

linear time complexity with DP.

linear time complexity with DP.

tree structure is no more! Now, at the start, we

calculate all needed results of our two functions from

tree structure is no more! Now, at the start, we

calculate all needed results of our two functions from  to

to  .

.

, this has a time complexity of

, this has a time complexity of  .

.

, or

, or  .

.

|

|

|

|

A matching |

Not a matching |

Red: maximum, green: maximal

.

.

in R is revealed, along with its neighbours

in R is revealed, along with its neighbours  in L (nodes in L that are compatible with v).

in L (nodes in L that are compatible with v).

, we have to either:

, we have to either:

with a node in

with a node in

at all

at all

|

A Brief History of Bipartite Matching |

|

Online bipartite matching was first studied in 1990, when online algorithms first became popular.

In the 21st century, web advertising became popular and proved to be a huge revenue generator.

Interests in online bipartite matching was rekindled: a lot of results were discovered and published within the last decade or so.

Did you find that interesting? Eh, me neither. |

, or “the fraction of the number of matched nodes

yielded by the optimal algorithm that our compared algorithm

could achieve”.

, or “the fraction of the number of matched nodes

yielded by the optimal algorithm that our compared algorithm

could achieve”.

to any compatible node in

to any compatible node in  as soon as it appears.

as soon as it appears.

Don’t let this algorithm anywhere

near the Food Allocation problem!

, we could do better.

, we could do better.

, we don’t have to fully match it.

, we don’t have to fully match it.

with many nodes in

with many nodes in  !

!

is a container with capacity 1

is a container with capacity 1

is a source of 1 unit of water

is a source of 1 unit of water

arrives, drain water from

arrives, drain water from  to

to  , always preferring the neighbour with the lowest current

water level, until either:

, always preferring the neighbour with the lowest current

water level, until either:

is full, or

is full, or

is empty

is empty

|

|

Our first node arrives!

It’s neighbouring three L nodes, so we distribute water to each evenly. |

|

|

Another node arrives!

It’s neighbouring an empty L node, and an L node we’ve already filled.

First, it fills the top node to 33%, then it fills the top and middle nodes evenly, until our R node runs out of water and both L nodes are 67%. |

-competitive.

-competitive.

.

.

times the maximum possible.

times the maximum possible.

-competitive.

-competitive.

-competitive?

-competitive?

for maximum bipartite matching.

for maximum bipartite matching.

times.

times.

as like a “capacity” for L nodes.

as like a “capacity” for L nodes.

for online b-matching.

for online b-matching.

but it converges to

but it converges to  for really large values of b.

for really large values of b.

arrives, match it with a neighbour in

arrives, match it with a neighbour in  with the highest remaining match

“allowance” (the most free capacity).

with the highest remaining match

“allowance” (the most free capacity).

maximising:

maximising:

is bidder

is bidder  ’s bid

’s bid

is the fraction of

is the fraction of  ’s budget that has been spent so far

’s budget that has been spent so far

, where:

, where:

is the amount of money spent

is the amount of money spent

is the total budget of

is the total budget of

|

Theorem Mehta, Saberi, Vazirani, Vazirani, FOCS 2005 |

|

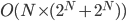

The competitive ratio of the factor-revealing

LP algorithm is |

agents, who want bits of the cake, and prefer certain

parts of the cake more than others.

agents, who want bits of the cake, and prefer certain

parts of the cake more than others.

Mmmm cake

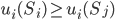

, that represents how much the agent likes each part of the

cake.

, that represents how much the agent likes each part of the

cake.

, we need to find the integral of our valuation function,

, we need to find the integral of our valuation function,  :

:

of the entire cake, according to their own utility /

opinion.

of the entire cake, according to their own utility /

opinion.

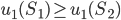

for any agent

for any agent

pieces.

pieces.

for any agent

for any agent

for any agent

for any agent

, but not

, but not  .

.

for all

for all

for any

for any

, and this is

, and this is  :

:

is false for all agents, and

is false for all agents, and  .

.

and adjusting the values to make this right:

and adjusting the values to make this right:

, because now

, because now  .

.

.

.

, proportionality is equivalent to envy-freeness.

, proportionality is equivalent to envy-freeness.

, but not

, but not  .

.

for all

for all

for any

for any

:

:

.

.

.

.

, proportionality implies envy-freeness.

, proportionality implies envy-freeness.

, we can use I Cut, You Choose.

, we can use I Cut, You Choose.

, there’s a whole range of protocols we can

use.

, there’s a whole range of protocols we can

use.

|

Discrete cake cuts (must cut at certain spaced-out distances) |

Continuous cake cuts (can cut at any arbitrary distance) |

|

Steinhaus 1943

Selfridge-Conway 1960, 1993

Brams-Taylor 1995 (unbounded cuts)

Aziz-Mackenzie 2015 (extendable to any |

Stromquist 1980 |

:

: